The A.I. Ownership Problem

There's a big big difference between whether you own the robot that can do your work and your company owns the robot that can do your work

AI makers like OpenAI, Microsoft, and Meta offer a future of abundance, convenience, and creativity through Artificial Intelligence. Their AI; their particular flavor of Large Language Models (LLMs).

Of course, they're all about the same, delivering about the same intern-quality of writing, the same vanilla grammatical structures, and about the same level of hallucinations — i.e., they are prone to make stuff up instead of saying — like a lot of guys — "I just don't know."

To thwart their Star Trek vision of the future is to be accused of being a "Luddite," which is supposed to be a bad thing because they broke up looms that exploited child labor, drove down the quality of goods, and literally starved their families to death. Ah, but the abbreviated label makes for such a vivid and potent image of someone who is against technology and progress and all that is good and wholesome in life.

But what they don't want to discuss is what Justin Wolfers describes as the Ownership Problem vis a vis AI. Wolfers is a professor of policy and economics at the University of Michigan. He brought up what he called The Ownership Problem during a recent interview with Scott Galloway and Ed Elson on the Prof G Markets podcast.

Wolfers believes the AI Ownership Problem is actually the most important and transformative social and economic issue confronting this and future generations.

Unfortunately, certain politicians, their illegal policies, and their efforts at terrorizing the population are front-and-center of most everyone's attention in the United States when the AI Ownership Problems will most likely have the greatest and most long-lasting impact on today's society and for generations to come.

The Ownership Problem is one about who gets to enjoy the fruits gained by the "robots" used by consumers. Let's say you can use a robot (ie, AI) to do your work; then, you can chill, enjoy life, and be however creative you choose. You feel economically safe and secure in your life because you own the robot. However, what if the company for which you currently work owns the robot?

Well, if the robot can do exactly the same work as you at close to no cost relative to the salary and benefits the company pays you, do you think you'll still have a job after the company's purchase of the new tech.

The labor market answered the question as early as the 1970s, when automation began replacing factory jobs. Automation also facilitated globalization in the early 2000s. Though globalization did affect the loss of entire industries at local levels (e.g., the furniture industry of North Carolina), automation was the single greatest contributor to job attrition broadly across America.

That's why the current regime's prognostications to bring manufacturing jobs back to the US is so much hot air: due to labor costs in this country, business owners and investors are merely going to use lower-cost machines to do the work. (See my article about Dark Factories).

Now, instead of manual labor, the robots are going after cognitive labor; i.e., white collar jobs. Anecdotally, it's the reason there are nearly 20% fewer job openings for recent college grads than a year ago: companies are giving AI to more experienced workers and expecting them to do more with less.

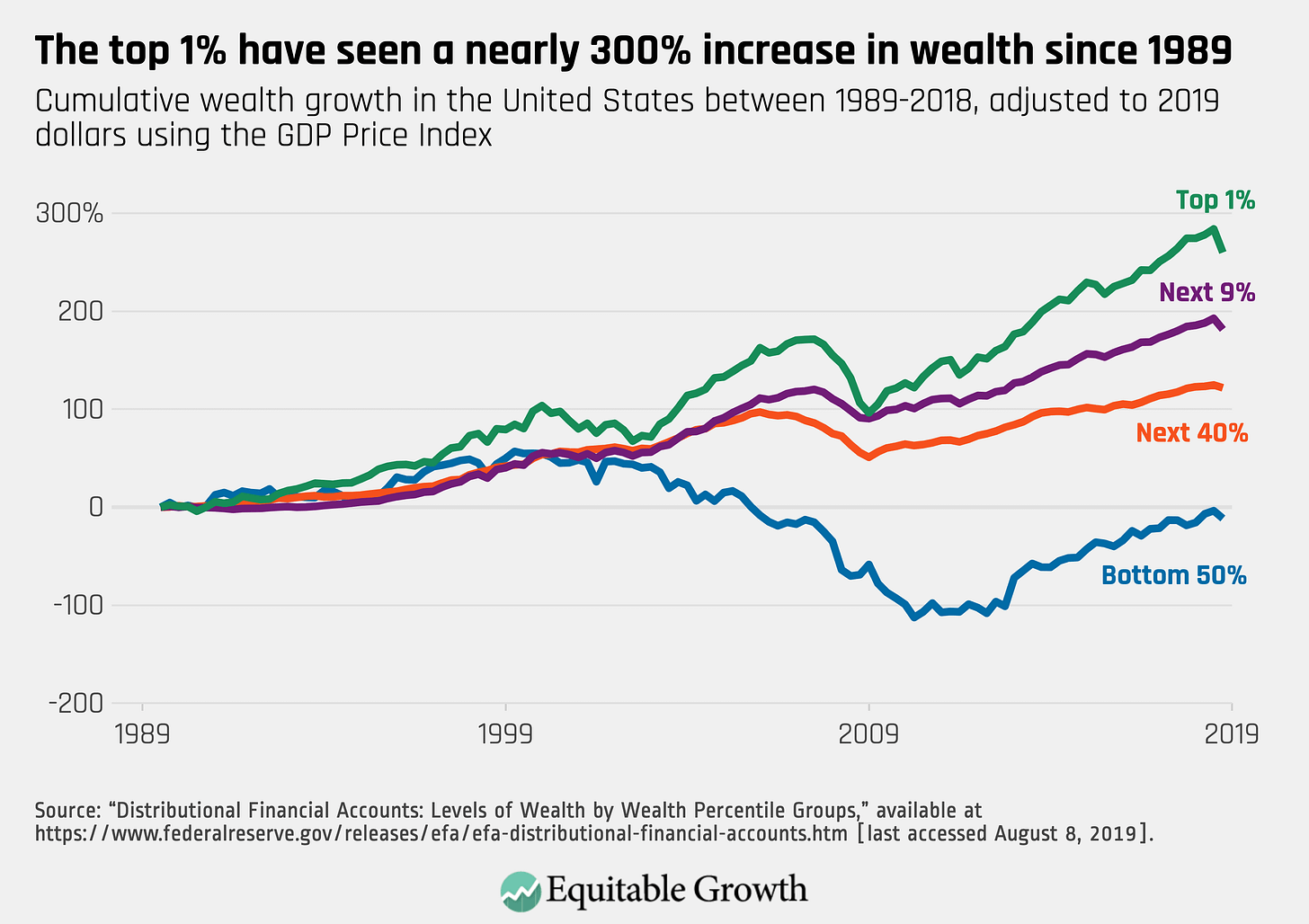

And while we may hope that progress in AI adoption will reap a golden era of prosperity for knowledge workers, think again. We've already seen since 1980 the spoils of prosperity from the personal computing age through the internet-ization of everything go to the top 10% of the population, and an even greater proportion to the top 0.1%.

We only have to witness how the owners of capital have infiltrated Congress and the world's richest man could buy the Presidency. Further, with half the number of companies listed in American stock exchanges compared to 1997, the capital upon which the AI makers are suckling is private equity; citizens — especially young people — are completely locked out of even partial ownership of the companies through shares.

The answer, unfortunately, lies with citizen action. Citizens have to vote in the kind of people who understand and are willing to grapple with the level of economic inequality that has poisoned the government and society.

Otherwise, many of us, no matter how well educated, risk being sidelined in our own democratic society.